Police officers form a ring around a group of youngsters in Bab al Had square in Rabat. At first, there are four, five, six officers but soon a dozen are on the scene and more keep coming, their anti-riot shields held up, trapping the bodies in the middle.

Douaa Bourhaba is in that circle, hammering against the polycarbonate shields with her hands, arms and knees. She fights back even as the police engulf her and the other protesters. Watching her comrade get arrested lights something in her. “I was scared. But my fear was smaller than my anger and my sense of responsibility,” she says.

The 20-year-old masters student was one of hundreds of people who joined protests in Morocco’s capital city after news spread that eight women had died, in just ten days, while undergoing caesarean-section operations at a government-run hospital in Agadir, a city 477km (296 miles) away from where Bourhaba lives.

So many deaths in such a short span of time, at a failing healthcare facility – while the government reportedly spent billions of dollars on the football World Cup preparations – led to public anger. In mid-September 2025 unrest spread from Agadir right across the north African country.

“We were already angry about unemployment and education, but maternal deaths hit a moral nerve,” says Houria Bamensour, representative of the Health Coordination Committee, a collective of health sector unions, based in Agadir. “Protests stopped being abstract. Health became the symbol. If the state can build stadiums and host global events, it can keep mothers alive.”

Those protests became known as Gen Z 212 (the international dial code for the country is +212), connecting Morocco to the Gen Z protests, a wave of uprisings led by young people around the world that started in Bangladesh in 2024 and continued through 2025. But there are parallels too with the February 20 Movement that marked the beginning of the Arab Spring in Morocco 15 years ago.

Whether in 2011 or in 2025, what moved people to take to the streets was not only policy failure but rage spurred by a feeling of neglect. Irene Fernández-Molina, senior lecturer in international relations at the University of Exeter, explains that the deaths were “the sort of trigger that makes people take to the streets almost immediately”. It was, Fernández-Molina says, “al hogra” – an Arabic term used in Morocco to describe the feeling of humiliation and indignity that occurs when authorities abuse their power and deny people basic rights.

That feeling encapsulates why a feminist cause – maternal mortality – slipped into the social debate and turned into a public reckoning with the government.

A health system under pressure

Despite a national health strategy that was set out in 2020 to invest $2.5bn into the public healthcare system, the deaths in Hassan II Hospital in Agadir cast a spotlight on persistent health inequities in Morocco.

According to the latest World Health Organization data from 2023, Morocco has 7.9 physicians per 10,000 people. The UN agency recommends a minimum of 10 per 10,000. Healthcare is available through a network of public facilities and from the private sector, but the public healthcare system, which provides the vast majority of care to Moroccans, attracts just 42% of healthcare spending.

“Most people cannot afford private insurance in Morocco,” says Noor Ammar Lamarty, a lawyer and self-identified Gen Z feminist. “Women’s suffering in healthcare exposed a broader humanitarian collapse, making women’s reproductive rights legible as the human rights that were being neglected by the government.”

Fernández-Molina agrees that the deaths managed to connect with people who may not otherwise be incensed by high maternal mortality: “These were women's deaths, but [they] weren’t seen only as a feminist cause. It was about everyone”.

The focus of Gen Z 212 on socio-economic change marks a shift to the demands made by the youth in 2011, where they sought political change. Some parts of the February 20 movement called for Morocco, which has a powerful monarchy which remains the country’s ultimate political authority, to devolve real power to an elected government. This time around, there was no mention of the monarchy or the king. Fernández-Molina, whose work focuses in part on conflict in the Maghreb, argues that this is because the protest leaders conceded after 2011 that political demands “do not translate into real change in their lives”.

“Women in the impoverished rural areas feel the consequences of neglect in the public healthcare services much more directly than the creation of a new quota for political parties to run more women candidates in the elections,” says Fernández-Molina, referring to constitutional amendments introduced after 2011.

In a country where a quarter of Moroccans are considering emigrating in search of better living conditions – citing unemployment, rising living costs, and declining trust in public services as the main reasons – the demand was less about abstract political reform than about the conditions of everyday life. "The message was not 'I want to be free'," the lawyer explains. "It was: 'I am telling you what freedom should look like: better healthcare, education.”

The eight maternal deaths were a reminder that development was happening at two different speeds, in what felt like two different countries: the rapidly modernizing one that was able to hold international competitions like the world cup, and the one without sufficient access to quality jobs, education, and public services. But also that Gen Z was no longer willing to wait for the government to reconcile the pace of modernization with meaningful improvements in everyday living standards.

From grievance to crackdown

During the uprising across September and October, Gen Z 212 protesters were met with “excessive and disproportionate force”. Human rights groups accused security forces of killing or injuring over a dozen young people. By the end of October, 1,400 had been arrested and more than two thousand people were being prosecuted.

Reflecting on the events of last year, Rim Akrache, a psychologist from Casablanca who participated in the protests, says that she believes the demonstrations lost sight of the women whose death sparked the movement. “We don't even talk about women's rights,” Akrache says. “A lot of people forget why it started, but we went into the streets because eight women died.”

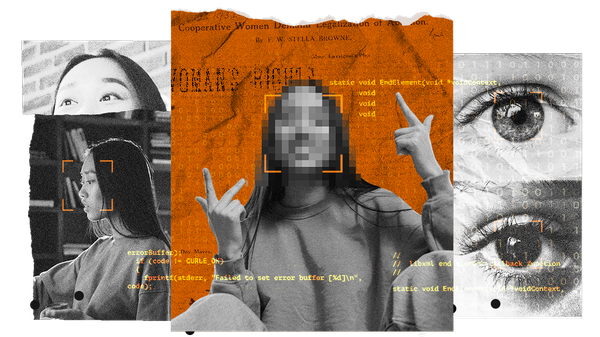

She says that women and LGBTQ+ activists suffered a “heavy backlash” following the protests, and confirms reporting on the harassment and abuse of women protesters. “I saw a lot of feminists and queer activists in the streets during the protests. It was really nice, but they have been silenced. The police accessed their phones and used the content to criminalize them,” she says.

In December, The Observer reported that Pegasus, an infamous no-click spyware developed by an Israeli company, had been installed onto some Moroccan activists’ phones. The technology is called “no-click” because the device owner doesn’t have to engage with it in any way for it to work.

Following the protests, Morocco’s minister of health, Amine Tahraoui, outlined plans to reform the public healthcare sector and invest more in hospitals, building new facilities and restoring old ones. Several key staff at Hassan II Hospital in Agadir were suspended (though some were later reinstated), and Morocco’s 2026 budget, approved by the palace, includes a 16% increase ($15bn) in allocations for health and education over the previous year’s spending.

Almost 15 years after Tunisian street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire – an act that sparked protests that swept across the Arab world – young people were back on the streets, facing off once again with the authorities and seeking to shift power toward the Moroccan people.

This may not have happened in radical ways, but as Bamensour of the Health Coordination Committee says, “Gen Z wasn’t asking for miracles.” Reflecting on what the deaths of eight women in childbirth have come to symbolize and why they held such power to mobilize, she adds: “What scared authorities wasn’t just the protests. It was the framing. We were asking for functioning hospitals, trained staff, accountability, and dignity.”

“Agadir became a breaking point. These women were not invisible,” she says. “They had names, babies, families, and their deaths felt preventable. Maternal deaths became the clearest indicator that the social contract was broken.”

How we made it

12,000 kilometers travelled

48 liters of tea drank

12 NGO and academic reports read

10 people interviewed

5 hours of interviews

4 hours staring at a blank screen

Visuals by Ethan Caliva, edited by Eliza Anyangwe and Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff

Visuals by Ethan Caliva, edited by Eliza Anyangwe and Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff