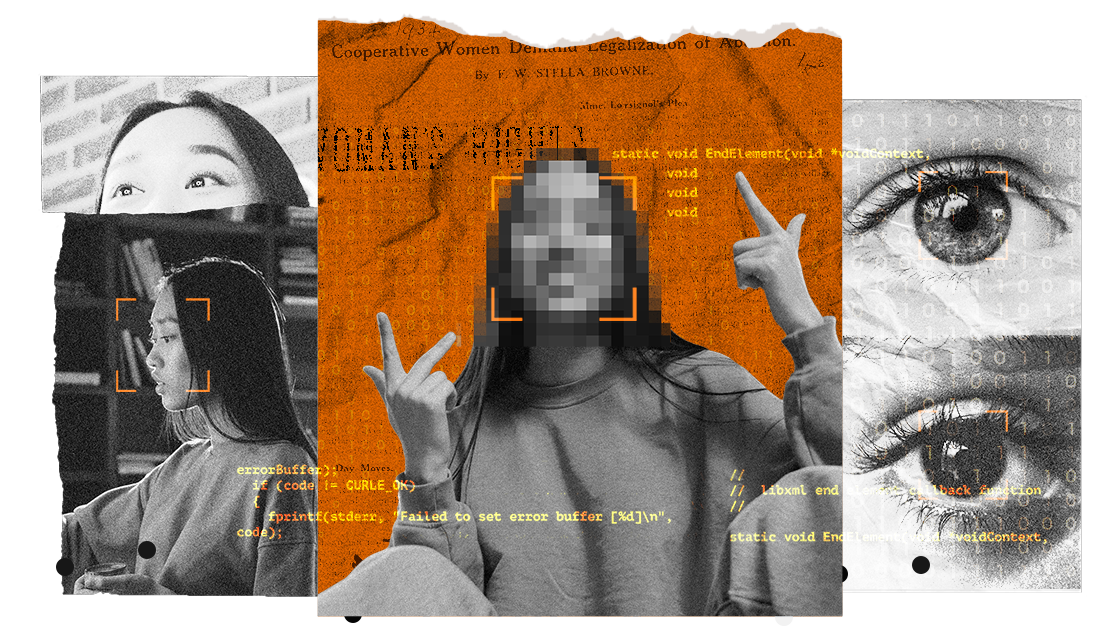

Carmen Lau stared at a naked, female body on her computer screen. A body that had her face but in fact, wasn’t her at all. Lau was looking at the scanned copy of a letter, which along with the nude image, had her name and details of sexual services she was supposedly selling.

By the time Lau was looking at the fake image, over a dozen letters just like it had been mailed to all the apartments in her building. A few more had been sent to homes down the road from where she lived in Maidenhead, a picturesque town about an hour's drive from London, UK.

Lau, 30, is an exiled pro-democracy activist from Hong Kong. In her 20s she became a district councillor in the region, in 2021, after China imposed a national security law that led to the arrests of hundreds of activists and opposition figures, she quit, telling Hong Kong Free Press that she refused to “become a pawn of tyranny”. Soon after, she fled to the UK. From exile, Lau has continued to speak out against Beijing’s crackdown on civil society and press freedom in Hong Kong, and against its actions in her host country.

These activities, she believes, have made her a target – and not for the first time. Last February, former neighbours of Lau’s received letters purporting to come from the police, which offered a £95,000 reward to anyone who’d hand her over to the Chinese embassy.

But this last time, Lau told Fuller, the tactics were chosen specifically because she is a woman. “This time is different because it escalated to gender-based violence.”

The use of sexualised deepfakes, disseminated where she lived, had a chilling effect. “At the beginning, it was very uneasy for me to even go out on the streets and see my former neighbours,” Lau said. “The images on the letters look very authentic. I didn’t know who believed the letters were real.” She cannot be certain who was responsible, but she believes the letters were sent by bad actors from China.

If she’s correct, what Lau experienced is a phenomenon researchers call “gender-based digital transnational repression”. Here’s what you need to know about what that looks like and why it matters.

‘Gender-based transnational repression’ sounds awful, but what is it?

Let’s start with the second part. Transnational repression is an umbrella term for the tactics that governments use to reach across borders to silence dissent among exiled citizens and activists in the diaspora.

There have been significant examples of it in the last decade, including the case of Saudi women’s rights activist Loujain al-Hathloul, who was kidnapped by authorities in the United Arab Emirates in 2018 after three former US intelligence officers, contracted by the United Arab Emirates government, allegedly hacked her phone and tracked her movements using sophisticated surveillance systems.

Meanwhile, exiled Bahraini human rights activist, Mariam Al Khawaja, has been the victim of state-sponsored digital harassment, including having false rumours spread about her online stating that she had had an abortion, had fake breasts and was promiscuous.

Researchers, like those at Canada’s Citizen Lab, who study how digital tools are used against human rights defenders, have observed that “state and state-affiliated actors weaponise gender as a tool of repression against women human rights defenders” – which is what Al Khawaja and Lau experienced. The goal, the Citizen Lab writes, is to use patriarchal norms and women’s own bodies or sexuality to shame them or call into question their honor, which can lead to more violence and discrimination.

States targeting women activists is a tale as old as state repression itself. In 1914, British police covertly photographed women in the Suffragette movement. During the Cold War, Stasi “romeos” from East Germany seduced often vulnerable women in the west for “sexual blackmail”; some of these romantic relationships lasted close to a decade. But tactics used by authoritarian governments have kept pace with changes in technology, making it easier for them to intimidate their opponents from afar.

And why does it matter?

The number of authoritarian governments is rising, with nearly 40% of the world’s population now living under authoritarian rule, according to the latest Democracy Index, published by the Economist’s Intelligence Unit. The EIU reports that autocrats “also appear to be learning from each other about how best to protect themselves and neutralise opposition”.

Simultaneously, as migration increases and technological innovation accelerates, there are more people who can be easily targeted in this way. In fact, the conditions for transnational repression are so optimal right now that it’s been called a “golden age”.

“It's cheaper and easier [for autocrats],” Noura Aljizawi, a Syrian activist and researcher at The Citizen Lab, told Fuller. “They can find ways to target all women in the movement without even bothering to deploy a lot of resources.” For example: if a government wanted to spy on a woman in the 20th century, it would have had to fork out a salary to an agent hired to take photos of her. Today, a state can buy software to hack her phone or computer for as little as $70.

The consequences of gender-based transnational repression are serious – for the women attacked but also society. Aside from the psychological distress caused by being surveilled, hacked, intimidated or harassed, digital violence leads women to withdraw from public life and even public spaces. Lau, for example, has been “taking a break from work and public life” since December 2025.

When women withdraw it’s bad for democracy, bad for the even more vulnerable people they tend to advocate on behalf of and bad for all citizens as fewer demands for accountability embolden authoritarian leaders.

After Carine Kanimba, a political activist and lawyer who is also the daughter of Paul Rusesabagina, the hotel manager who famously sheltered over a thousand people during the Rwandan genocide, had her phone hacked with a software notorious for helping governments snoop on human rights defenders, she found herself impacted for years.

“The way it's affected me in the long term is that self-censorship creeps into conversations with friends and family,” she told Fuller. “It's the lowering of your voice when there's no reason to, but somehow you feel like someone, somewhere far away is listening."

But surely surveillance or malware affect everyone the same way?

Yes. But the ways in which they’re used to cause harm can be gender-specific.

Eva Galperin is director of cybersecurity at Electronic Frontier Foundation, a non-profit “defending civil liberties in the digital world”. She told Fuller the story of a woman, living in Saudi Arabia, who was hacked by “government actors”. They stole a photo of hers and published it.

“It was of her in a hot tub, wearing a bathing suit and no head covering – which was a completely normal thing for her to do in that context, at home and only around women,” Galperin explained. “But that got her death threats when it was made public.”

“Culture and context matter a lot,” Galperin added. “A lot of the kind of imagery that you might think might be harmless in certain contexts might get someone killed.”

Is anyone doing anything about this?

As Paige Collings, a lawyer at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, put it: “There are [regulatory] mechanisms, but I think they're probably not adequate enough, and they're not implemented in the way that they should be.”

Aside from international treaties and laws, such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, individual countries often have their own legislation that should protect women from tech-facilitated violence and transnational repression. But the Citizen Lab found victims were frustrated by what they perceived as police inaction or apathy.

Accountability is also hard to get.

“Even when governments get hacked, it’s hard to prove,” explained Anwar Mhajne, a political scientist focusing on feminist security studies. Discovering who is behind an attack is difficult, she said. “For example: are they Russian hackers? Or were they paid by the state? … The attribution problem makes it very hard to intervene, especially when it's cross-border.”

There might be a glimmer of hope: in November 2025, the G7 group of countries pledged to combat transnational repression for the first time ever.

Realistically though, greater coordination can only do so much to fix the problem as long as the tools that governments use to repress activists across borders are accessible and in demand.

What do you mean ‘tools’? What are they and who is making them?

Governments buy equipment and software from companies such as Palantir, which supplies US Immigration and Customs Enforcement with multiple surveillance technologies, or buy data about target individuals or groups to learn more about their patterns and vulnerabilities.

Let’s start with the equipment. Perhaps most infamous of all is zero-click spyware. Its name refers to its nature: it can access a person’s device without them needing to click on anything to activate it. Because of this, it can be used undetected.

Ever heard of Pegasus? This spyware was developed and is licensed by the Israeli company, NSO Group. According to Amnesty International, it “has been used to facilitate human rights violations around the world on a massive scale”. A 2021 investigation by the Washington Post revealed that Pegasus spyware had been placed on Jamal Khashoggi’s wife’s phone not long before his murder.

The role of data brokers in facilitating transnational repression is much less recognised.

Data brokers are companies that collect information about individuals from apps, websites, public records, etc. and then share or sell that data onwards. The companies trading in data are scattered all over the world, which makes it difficult to hold them, and their customers, accountable. “It's a black box,” said Galperin. “Even the data brokers don't necessarily know where their data comes from because data is sold and re-sold and re-resold and re-resold after that.”

This all sounds kind of illegal. Is there any regulation?

In the US, there’s a law that stops data brokers from selling information to “foreign adversaries”. But there’s no federal law to regulate the data broker industry as a whole. In Europe, things look a little better: under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), data brokers need to make sure that they’re collecting data legally – and being transparent about it.

Things get trickier when it comes to regulating commercial spyware companies that make software like Pegasus. Despite a 2022 EU parliamentary inquiry that produced 136 findings and recommendations against illegal spyware use, no concrete legislation has followed.

In 2025, Dutch newsroom Follow the Money revealed that the EU had trickled tens of millions of euros in subsidies to commercial spyware companies over about 10 years.

“All the governments want to continue using the spyware,” said Galperin. “You tell them to stop buying it, they will find a reason to drag their feet.”

We’re cooked! Are there ways women and gender-diverse activists are protecting themselves?

Yes. Like everyone who wants to be safe online, they’re using two-factor authentication, stronger passwords and encrypted messaging platforms. Besides this, as Hong Kong activist Lau told Fuller: “There’s nothing I [can] do”. UK police opened an investigation into the letters that offered a bounty for her. That investigation is still ongoing.

In the meantime, several of the activists, campaigners and researchers Fuller spoke to talked about what it takes to heal after the violation. The Citizen Lab found in its study of gender-based digital transnational repression that women shield themselves psychologically by leaning into their community: relying on others helps them reframe how they think about the attacks and build resilience against them.

"Working with activists and journalists who were targeted in a similar way to me was a healing process," says Aljizawi, the Citizen Lab researcher who herself was a victim of gender-based transnational repression. "I can turn this paranoia and anger into something more impactful to help other people, reveal these kinds of atrocities and fight back. The more we open spaces to talk about it, we develop our immune system."

How we made it

8 hours of recordings

7 interviews completed

2 spyware companies that refused to talk

1 moment of total shock

Visuals by Ethan Caliva, edited by Eliza Anyangwe, Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff and Erica Hensley

Visuals by Ethan Caliva, edited by Eliza Anyangwe, Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff and Erica Hensley