Dhaka, Bangladesh – Rehana Begum lay ill in her cramped two-room apartment on the outskirts of Dhaka on election day. Her sickness meant she would not be participating in Bangladesh’s first election since the student-led uprising in July 2024 that toppled Sheikh Hasina’s 15-year rule. In any case, Begum could not afford the journey back to her village to cast her vote. These days her wages, earned working in a garment factory in the capital’s industrial outskirts, barely cover her rent, food and other living expenses.

Before Thursday’s elections, Begum says she and her colleagues talked about which political parties they would be voting for. Their favourite depended on which one promised to make their lives better. “Whomever wins, we want the next government to increase our wages, because with the salary I earn right now, it is difficult to support my family,” she says.

On Friday, 12 February, it was announced that the centre-right Bangladesh National Party (BNP) had won by a landslide, securing two-thirds of the parliamentary seats. Its leader, Tarique Rahman, will be sworn in on 17 February, after almost two decades in self-imposed exile.

This election marked the end of a transition period, led by Nobel Peace Prize winner, Muhammad Yunus, and the beginning of what many hope will be a more democratic, prosperous future. But Begum, 40, is less sure. She joined the deadly protests in 2024, believing that the movement would bring about change for everyone. But despite Bangladesh’s dependence on the garment sector, she has yet to see it.

The oppressive system

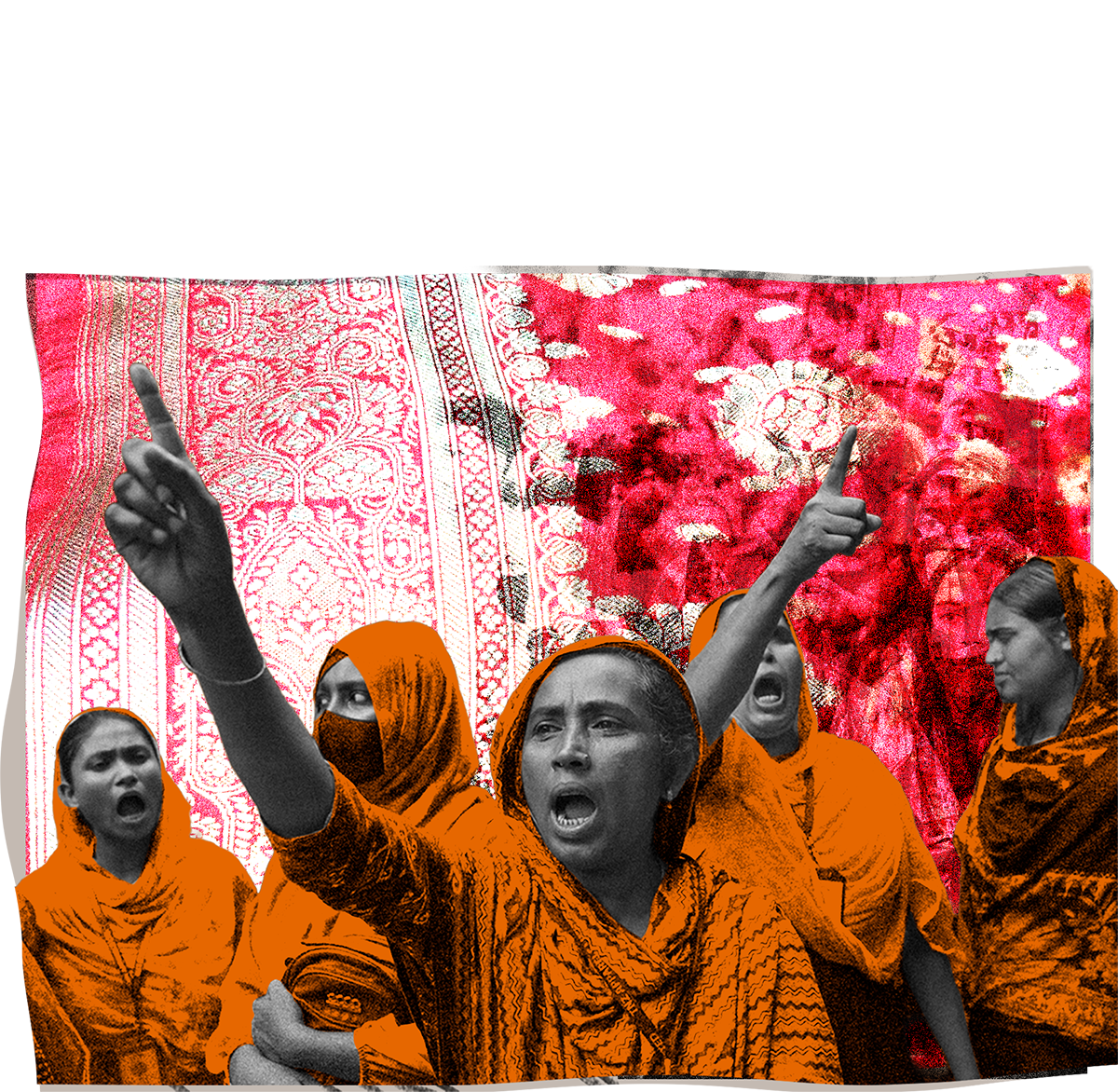

The July or Monsoon Revolution, as the uprising has become known, gets its name from the rainy season and began as student-led protests against job quotas in government positions. As security forces cracked down, firing rubber bullets, tear gas and live ammunition, the movement’s demands expanded. So did its support.

Students were joined on the streets by lawyers, teachers, rickshaw drivers, day laborers and opposition leaders. What began as a call for quota reform turned into a broader indictment of corruption, economic hardship and democratic backsliding under Hasina. By August, protesters were calling for the prime minister’s resignation.

Garment workers were not directly affected by quotas, explains Kalpona Akter, executive director of the Bangladesh Centre for Workers Solidarity. But, they had many unaddressed grievances such as low wages, long hours and unsafe working conditions.

Women have long been the public face of Bangladesh’s garment industry – the second largest in the world by export value. While numbers have fallen in recent years, recent data suggests they make up roughly half of Bangladesh’s 4 million garment workers. Most of them are rural migrants, like Begum, whose labour has helped to normalise the “visibility and mobility” of women in Bangladeshi cities, according to New York University professor Dina M Siddiqi.

But persistent pay inequality, sexual violence, harassment at work, and exclusion from leadership roles – all against the backdrop of the crippling price of food in 2024 – prompted female leaders from over 120 factories to come together when protests spread across the country. It was easy to mobilise workers.

“The students were fighting discrimination. Garment workers face discrimination every day,” says Akter, one of the most prominent labour activists in Bangladesh, who Hasina reportedly once called an enemy of the nation. “Women really wanted to see a change. We wanted to get rid of the oppressive system.”

So, Akter says, the labour leaders decided to mobilise workers into solidarity groups that would march and bring food and water to the protesters. By the end, they’d also bear witness to dozens of killings, including of their own colleagues.

Joining the revolution

On 4 August, Begum was starving and angry. Factories had been shut for several weeks amid the protests. She left her small, cramped home and walked toward the highway in Dhaka, where hundreds of other workers had already gathered, waving placards. Soon, she says, the bullets came. “I saw people falling to the ground. I heard them screaming. Three of my colleagues were killed that day. I could have been one of them,” she says.

The mother of five had moved to the city only the year before, from Gaibandha, a poor district in the north where there are few jobs and even fewer options for women. Back home, she worked in the informal sector as a tailor but says she could never make more than 8,000 taka (65 USD) a month – half of what a man in formal employment made in Bangladesh in 2024.

In the capital, she hoped to double her income. She wanted her children to grow up in better conditions and maybe even become something other than garment workers. After the family moved in January 2024, she says she found a job as a sewing machine operator at a factory that exports clothes to international brands such as Walmart, GAP, American Eagle and H&M.

Initially, her wages did rise as she’d hoped. Enough to keep her children in school and pay rent. But by July, things were getting difficult. Food prices had been rising for a while but when the protests began, disruption to the supply chain sent prices soaring across the south Asian country. Rents were also rising in the densely-packed megacity.

So Begum began working longer hours without proper breaks, in extreme heat and humidity and under constant pressure from her supervisors to meet daily targets. Even then, she says, her take-home pay of around 20,000 taka ($163) with overtime was no longer enough to live on. Despite the brutal force with which security forces had been responding to the student protesters, Begum felt compelled to join.

“I was scared. But I was more angry than scared. If they [students] wanted a better country, so did we. That’s why I risked my life. I joined to express solidarity with the students.”

On 5 August, the day after Begum joined the uprising, Hasina left the country, fleeing in a helicopter to India. By then, over 1,500 people had been killed and thousands injured. Earlier this month, Hasina was sentenced in absentia to 10 years in jail.

‘Where did the women go?’

Things seemed to be looking up on the factory floor.

“Everyone was happy when Hasina fled. It felt like we had succeeded,” Begum says, adding without irony: “I noticed that our supervisors at the factory hurled fewer abuses at us.”

But by late August, to bounce back after weeks of closure, Begum says production line workers – made up disproportionately of women – faced heavier workloads. She tried to rationalise: “I thought if the wages increased, then I would not mind working extra”.

Soon, garment workers were back on the streets, demanding that the interim government increase wages by 15%, a figure they’d been campaigning for since 2023. Police, once again, responded with lethal force. There were other signs too that Bangladesh may not yet have embraced the revolution’s anti-discrimination rallying cry.

Hailed as heroes in the new political landscape, male students seemed to be moving from protest to participation. They were consulted on reforms and offered appointments in the interim government. They formalised their political ambitions by creating a new party to stand in the 12 February elections – and aligned themselves with the leading Islamist party Jamaat-e-Islami (who, in February, claimed that women are unfit for leadership).

Despite their equal participation in the uprising, women were beginning to find themselves sidelined and erased in the movement's aftermath, reflecting a deeply entrenched view of women as subordinate in Bangladeshi society. There was even an event titled ‘Where did the women go?’, which highlighted the difficulties and marginalisation women leaders faced after the revolution.

Akter, who began working in a garment factory at just 12 years old, echoes these sentiments: “Girls and women disappeared from the forefront after the revolution. Their voices were merely used to fuel the protests and then they were sidelined. Press conferences became male-dominated and women were pushed to supporting roles.”

Bodies on the line

The garment sector may be considered the lifeblood of the economy in Bangladesh but professor of sociology at Dhaka University, Samina Luthfa, says “female workers were never considered important as a block. They were always seen as bodies that were producing”.

“Most of the achievements [to improve working conditions] post-Rana Plaza tragedy were due to activists and workers themselves fighting on the streets for their rights,” Luthfa adds, pointing to the fact that many factory owners are also in politics or close to politicians, which often prevents reforms for workers.

As much as the marginalisation of women garment workers is about patriarchy and misogyny, it is also about class, Luthfa says. “Students were regarded as the heroes because of their class positions and their networks. No one cared for women workers and that is not new.”

When contacted by Fuller, Rezwan Selim, the vice president of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association, which represents Bangladeshi factory owners, calls the workers’ complaints of harsh and unsafe working conditions “total rubbish”. Bangladesh’s interim government’s press secretary, Shafiqul Alam, told Fuller that the women should be happy with the 9% hike that they received in December 2024, calling it “the highest wage hike in the history of Bangladeshi garment industry”.

What now, then? Luthfa says that the manifesto of the election-winning BNP includes “some feasible steps for the precariat [low-wage workers]” but adds: “If it translates to empowering the female workers is yet to be seen”.

The garment sector itself has had a rocky couple of years, compounded by a 37% tariff imposed by the US administration, which was later reduced to 20%. Bangladesh exports the lion’s share of its garments to the United States. Ahead of the election, the interim government secured tariff exemptions on some clothes and textiles and a further reduction in other tariffs to 19%.

Still, the question of the extent to which women will benefit hangs in the air.

Begum says she has developed anemia and suffers frequent illnesses due to the gruelling nature of her work. Asked what she’d like to see from the new administration, she says:

“I hope that the new government will come up with a better scheme for the workers. We were disappointed with the actions of the past governments. I hope it does not happen again. We hope BNP fulfills our expectations, increases our salary, so that our life gets slightly better.”

And she's clear on what will happen otherwise.

“We will take to the streets again if we have to.”

How we made it

190 kilometers travelled

18 hours stuck in traffic

16 people interviewed

13 hours of interviews

4 hours staring at a blank screen

Global context

What happened in Bangladesh is not unique or unprecedented. Across history and geographies, women have repeatedly slipped into blind spots once revolutions have ended, despite having played central or frontline roles.

As recently as 2021, during India’s historic farmers’ uprising, women lived in tents set-up at protest sites for months, cooking and taking care of their families – braving the cold, rain and police aggression.

But when the uprising ended successfully with the repeal of controversial farm laws, little changed for women. The reality is that most women farmers in India remain landless and their work as unpaid labourers persists.

The same pattern was evident during the Arab Spring. Women protested alongside men, risked their lives, endured imprisonment, and faced brutal violence. But once the uprisings subsided, they struggled to be heard.

Visuals by Ethan Caliva, lead photography by Kazi Salahuddin Razu/NurPhoto, edited by Eliza Anyangwe and Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff

Visuals by Ethan Caliva, lead photography by Kazi Salahuddin Razu/NurPhoto, edited by Eliza Anyangwe and Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff